Real-time and Lightweight Phishing Prevention based on SSL Certificates and User Authentication Forms

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

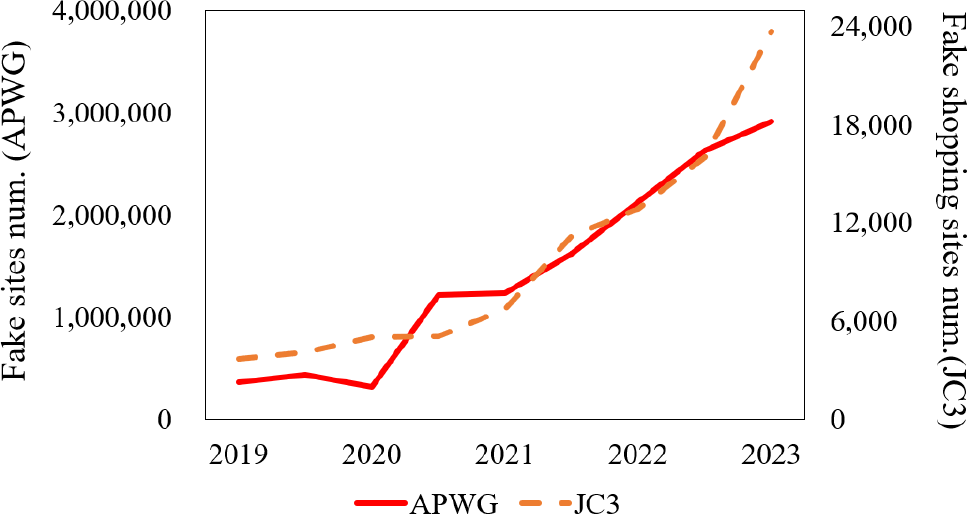

Phishing attacks, where attackers create phishing sites impersonating legitimate organizations to steal sensitive information, have been a persistent cybersecurity threat. According to Morgan's report, the global cost of cybercrime is projected to reach $10.5 trillion annually by 2025 [1]. In Japan, the Safer Internet Association reported 23,674 malicious shopping sites to the Japan Cybercrime Control Center (JC3) during the first half of 2023, marking an increase of 10,844 cases (84.5%) from 12,830 cases in the same period of the previous year [3]. Additionally, the number of phishing reports by the Anti-Phishing Working Group [4] increased significantly in 2023 compared to the previous year (Fig. 1). In the JC3 investigation as well, many phishing groups impersonating banks and credit card companies have been identified [5]. In 2023, damages from illegal money transfers related to internet banking, suspected to originate from these phishing sites, reached the worst levels ever recorded. The number of reported incidents hit an all-time high of 5,578 cases, with unprecedented damages of 8.73 billion yen, representing the most severe financial impact to date [6].

Additionally, damages from credit card number theft through fake shopping sites and phishing sites continue to rise. A survey by the Japan Consumer Credit Association on fraudulent use of domestically issued credit cards revealed that the total amount of fraudulent transactions reached 540.9 billion yen in 2023, marking the highest recorded amount to date [7]. These alarming statistics underscore the urgent need for effective countermeasures against phishing attacks.

1.2 Objectives and Contributions

Previous research [8] [9] has proposed methods to detect phishing sites in real time using machine learning, but in reality these may be difficult to provide real-time protection because they does not take into account usability issues, such as delays in website browsing due to detection processing. To address these problems, we propose a lightweight and simple detection method that does not compromise usability. To construct such a detection technique, we conducted an extensive analysis of a large number of phishing websites. It should be noted that certificates are not only used for encrypting communication channels but also serve to verify the legitimacy of websites [10]. Our investigation revealed that a combination of certificate expiration dates and the presence of input forms provides an effective basis for detecting phishing. We implemented a Proof-of-Concept (PoC) system and evaluated both its detection capability and processing delay, confirming the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

This study focuses primarily on phishing sites targeting financial institutions and e-commerce platforms, which represent the majority of high-impact phishing attacks based on our dataset analysis. The main contributions of this study are:

- (1)An examination of certificate validity periods and other characteristics of phishing sites, based on a dataset collected from multiple sources.

- (2)Development and evaluation of a Proof-of-Concept (PoC) browser extension that provides real-time detection of potential phishing sites based on the identified characteristics.

- (3)A comparative analysis of the proposed approach with existing phishing detection solutions, highlighting its effectiveness and limitations.

This study provides insight into the usage patterns of certificates and user authentication form on phishing sites, and demonstrates the potential of a simple approach for real-time phishing detection. The proposed browser extension aims to offer a user-friendly and lightweight real-time tool that can complement existing anti-phishing measures, particularly for users without advanced cybersecurity knowledge. We are aware of the trend toward shorter certificate validity periods, and the CA/B Forum is moving toward shortening the certificate validity period to 47 days as proposed by Apple, Google, and Mozilla [11]. However, free certificates are moving even shorter, to six days [12], and this difference leads us to conclude that the method of combining a user authentication form and a certificate will remain effective for the time being.

1.3 Paper Organization

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews related studies on phishing site detection and analysis. Section 3 describes the data collection process and presents a detailed observations of phishing site characteristics. Section 4 presents the design and implementation of the proposed browser extension. Section 5 evaluates the performance of the PoC extension and compares it with existing solutions. Section 6 discusses the strengths, limitations, and implications of the proposed approach. Finally, Section 7 concludes the paper with a summary of key contributions and future research directions.

2. Related Studies

2.1 Studies on Identifying Phishing

Phishing attack detection has been an active area of research, with various studies proposing different approaches. One prominent line of research has focused on leveraging machine learning techniques to detect phishing sites automatically.

Das Guppta et al. [13] developed a hybrid feature-based model that combines URL-based, website-based, and domain-based features to identify phishing sites. Their model achieved high accuracy in distinguishing between legitimate and phishing sites by employing various machine learning algorithms such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest, and Gradient Boosting.

Maurya et al. [14] proposed a browser extension-based hybrid anti-phishing framework that incorporates feature selection techniques. Their approach aims to reduce the computational complexity and improve the efficiency of phishing detection by identifying the most relevant features. The framework uses a combination of machine learning algorithms, including logistic regression, decision trees, and random forests, to classify websites as phishing or legitimate.

In another study, Sultan Asiri et al. [15] presented PhishingRTDS, a real-time detection system for phishing attacks. Their approach employs a deep learning model deployed in a Docker container for efficient deployment and scaling. The deep learning model is trained on a large dataset of phishing and legitimate websites, allowing it to learn complex patterns and features for accurate classification.

Liu, Ruofan et al. [16] achieved highly accurate detection by combining PhishLLM, which was trained on a wide range of domain information and target brands, with OCR processing of brand elements.

Taofeek [17] evaluated phishing sites targeting Bank of America, PayPal, ABSA, DHL, and Microsoft Login using multiple machine learning models, analyzing five sites for each target.

These studies demonstrate the potential of machine learning techniques for phishing detection. However, most of these approaches rely on post-event analysis and blacklisting, which may not provide real-time protection against newly created phishing sites. Moreover, the computational requirements of these models can limit their practical deployment and accessibility.

2.2 Studies on Phishing and Their Certificates

In studies focused on real-time countermeasures, Torroledo et al. [18] proposed methods to identify malicious certificate usage based on certificate field characteristics. Drury and Meyer [19] noted that certificates from the same issuer often contain similar or identical field values, making it difficult to distinguish between certificates used by phishing sites and legitimate websites when both are issued by the same authority. Dong et al. [20] attempted to identify fake sites using machine learning, and mentioned the certificate validity period as one of the features that is effective in identifying fake sites. Recent papers on real-time detection using machine learning [21] have also attempted to detect phishing by calculating a risk score based on characteristics such as the validity of the certificate.

Sakurai et al. [22] focused on Certificate Transparency (CT) logs, which record newly registered certificates. They proposed a method to identify phishing sites based on CommonName analysis, while acknowledging limitations in handling wildcard certificates and leetspeak variations. They also emphasized the need to verify their proposed method with other datasets containing diverse phishing URLs, not limited to the openphish dataset.

2.3 Studies on Analysis of Phishing

In addition to developing detection methods, researchers have also focused on analyzing the characteristics and behaviors of phishing sites used in phishing attacks. Understanding these aspects can provide valuable insights for improving detection techniques and staying ahead of evolving threats.

PhishTank [23] and OpenPhish [24] are well-known community-based databases that collect and maintain repositories of phishing sites reported by users worldwide. These platforms serve as valuable resources for researchers and security professionals, allowing them to study the patterns and trends associated with phishing campaigns.

D&B Hoovers [25] is a commercial database that provides comprehensive business information, including company profiles, industry data, and executive contact details. While not specifically designed for phishing research, this database can be leveraged to analyze the entities and organizations targeted by phishing attacks, as well as the techniques used by attackers to impersonate legitimate businesses.

Ito et al. [26] proposed a novel approach to detect disposable phishing sites by analyzing their building costs from PhishTank, OpenPhish and D&B Hoover. Their method examines various factors, such as domain registration fees, hosting costs, and the use of free services, to identify websites that are likely to be short-lived and used for phishing purposes.

In a study focused on the Japanese context, Our study [27] conducted a trend analysis of phishing sites targeting Japanese users. Their research involved collecting and analyzing data from various sources, including open databases and researcher-identified sites, to understand the strategies and techniques employed by attackers in the Japanese phishing landscape.

These studies highlight the importance of analyzing phishing sites from different perspectives, including their infrastructure, targeting patterns, and cost-related factors. Such analyses can provide valuable insights into the evolving tactics of attackers and inform the development of more effective countermeasures tailored to specific threat landscapes.

2.4 Research Gap and Our Approach

While existing studies have contributed significantly to phishing detection, opportunities for improvement remain, particularly in addressing evolving threats. Many current solutions rely on post-event analysis, which may not provide real-time protection against rapidly evolving phishing tactics.

Machine learning approaches have revealed insights into various features that are effective in identifying phishing sites [28], which may lead to the development of simpler, more user-friendly tools that can use these features to detect phishing attacks in real time.

Our research aims to address these points through the following approach:

- (1)Focus on certificate characteristics: We focus primarily on certificate validity periods and related attributes, based on the observation that many phishing sites use short-lived certificates.

- (2)Focus on user authentication form: Focus on the fact that phishing sites require victims to fill out a form in order to steal information. It is highly likely that it is possible to identify whether a user's information is being stolen by looking at the attributes of the tag, but since attribute information was not the target of data collection this time, the results were confirmed through PoC Experimentation.

- (3)Real-time detection: Our solution aims to provide protection at the time of user interaction with a website, complementing existing post-event analysis methods.

- (4)Simplicity and accessibility: We develop a browser extension that is designed to be easy to use and understand, aiming for accessibility to a wide range of users.

- (5)Complementary to existing solutions: Our approach is intended to work alongside other security tools and practices, providing an additional layer of protection.

By addressing these aspects, our research explores the potential of a targeted, certificate-based approach to phishing detection. It aims to contribute to the ongoing efforts in developing localized and user-friendly cybersecurity solutions.

3. Data Collection and Observations

3.1 Data Collection

The data for this study was collected from the following sources:

- ・OpenPhish: A community-based repository of reported phishing sites.

- ・Fake shopping sites [29]: A dataset of fake shopping sites targeting Japanese users, collected through our previous research.

- ・Researcher-identified sites [30]: Phishing sites targeting Japan that directly lead to financial damage such as banks and credit cards, collected by a security researcher (KesagataMe@KesaGataMe0) and shared on social media.

- ・legitimate site: Banks, credit cards, shopping sites are major ones that appear at the top of search results. and cryptoasset exchange service providers registered with the Financial Services Agency.

These sources were selected to ensure a comprehensive and diverse dataset of phishing threats. While fake shopping sites and researcher-identified sites provided insights into Japanese phishing activities (targeting banks, credit cards, and online shopping), OpenPhish enabled validation of our approach's global applicability. The data collection period extended from December 27, 2023, to March 10, 2024, capturing both active and historical phishing sites. Additionally, URL analysis data from a previous study [29] was incorporated to enhance the dataset. We also collected data from 100 websites of banks, credit cards, shopping, and cryptoasset exchange sites as legitimate sites for comparison.

3.2 Observations and Key Findings

Our observations of the collected data revealed several significant patterns and characteristics of phishing sites. The key findings from our observations are as follows:

- (1)Data Collection Summary: The dataset comprised 1,047 unique phishing site URLs, with new sites appearing at a rate of 10 to 20 per day (Table 1).

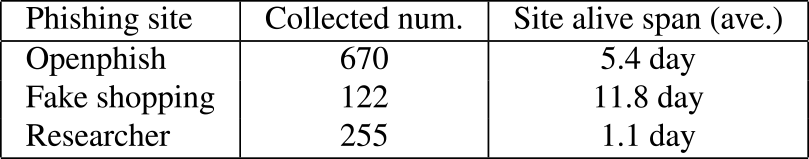

Table 1 Summary of Dataset Characteristics: Distribution of Phishing URLs Across Data Sources and Their Average Site Lifespan.

- (2)Certificate Validity Period Observations: A significant portion (89.8%) of the phishing sites used certificates with validity periods of 90 days or less. In contrast, most legitimate sites (98.0%) used certificates with validity periods exceeding 90 days (Fig. 2), reflecting the rigorous company verification process required for longer-term certificates. This distinct characteristic could serve as a valuable indicator for real-time identification of potential phishing sites.

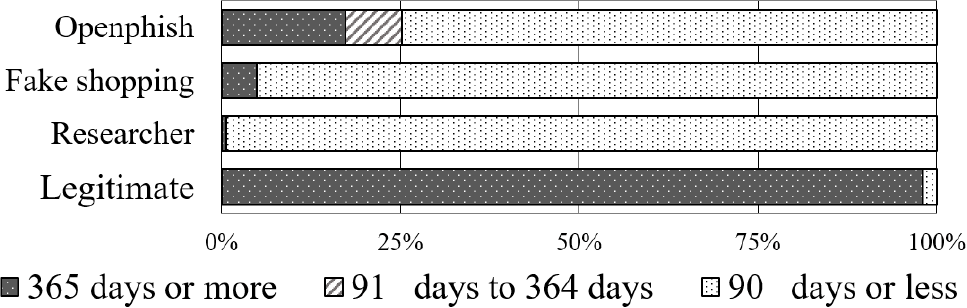

Fig. 2 Distribution of Certificate Validity Periods: Comparison between phishing sites (89.8% with ≦ 90 days validity) and legitimate sites (98.0% with > 90 days validity), showing distinct patterns in certificate duration. - (3)Certificate Issuer Patterns: The observations revealed that Let's Encrypt [31] (53.9%) and Google Trust Services LLC [33] (26.5%) were the most prevalent sources for the certificates used by the phishing sites(Table 2). Additionally, a large percentage (77.6%) of the certificates issued by Google Trust Services LLC originated from the CLOUDFLARENET netblock, suggesting widespread use of Cloudflare's free plan certificate services [32].

Table 2 Distribution of SSL Certificate Issuers: Observations of Top 10 Issuers for Phishing Sites (OpenPhish, Fake Shopping, Researcher-identified) and Legitimate Sites, Showing Distinct Usage Patterns.

- (4)SaaS and PaaS Platform Usage: A significant number of phishing sites were hosted on popular SaaS and PaaS platforms, requiring special attention in detection mechanisms.

- (5)User Authentication Forms: The presence of user authentication forms was a common feature among phishing sites, particularly those impersonating financial institutions.

These findings form the basis for our proposed browser extension design, as detailed in the following section. In particular, the validity period of a certificate can significantly indicate the characteristics of a phishing site.

The collected data and subsequent observations provided valuable insights into the characteristics of phishing sites, particularly in terms of their certificate validity periods and the issuers of the certificates they employed. These findings, particularly the distinct patterns in certificate validity periods and authentication form usage, form the basis for our proposed browser extension design. The following section details how we leverage these characteristics to create a practical solution for real-time phishing detection.

4. Simple Browser Extension to Detect Phishing Sites

Drawing upon the key findings from our observations summarized in Section 3.2, particularly the prevalence of short-term certificates (89.8%) and the consistent presence of user authentication forms, we have developed a browser extension designed to detect potential phishing sites in real-time. This extension leverages the identified characteristics of phishing sites, with a particular focus on certificate validity periods and the need for malicious websites to have input forms to steal user information.

Our approach directly addresses the insights gained from the data observations, incorporating the prevalence of short-term certificates, the common use of specific certificate issuers, and the short lifespan of phishing sites. We also consider the frequent hosting of such sites on popular SaaS and PaaS platforms, as well as the presence of user authentication forms as a key feature of phishing attempts.

By integrating these findings into our design, we aim to create a simple yet effective tool for real-time phishing detection. Simple here means that it is easy to install, and there is no need to set up a program execution environment on your computer, just install a Browser plug-in. The following subsections detail the design and implementation of our Proof-of-Concept (PoC) browser extension, demonstrating how we have translated these insights into a practical cybersecurity solution.

4.1 System Design

The core component of this study is a browser extension designed to detect potential phishing sites in real-time by leveraging the identified characteristics, particularly certificate validity periods. The extension targets the Google Chrome browser and serves as a Proof-of-Concept (PoC) implementation.

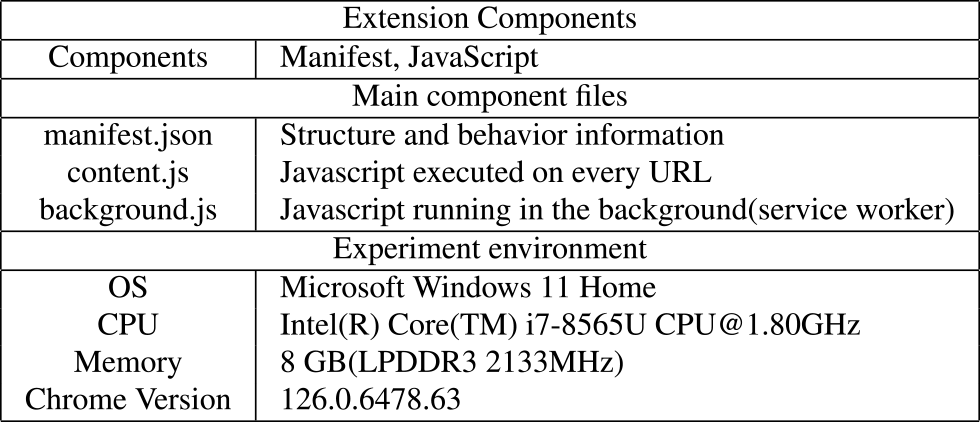

The extension's components consist of JavaScript, and the experiment environment was a laptop computer because the extension is intended for general users(Table 3). The extension is designed to run in the background to avoid affecting usability, specifically the time required to load web pages.

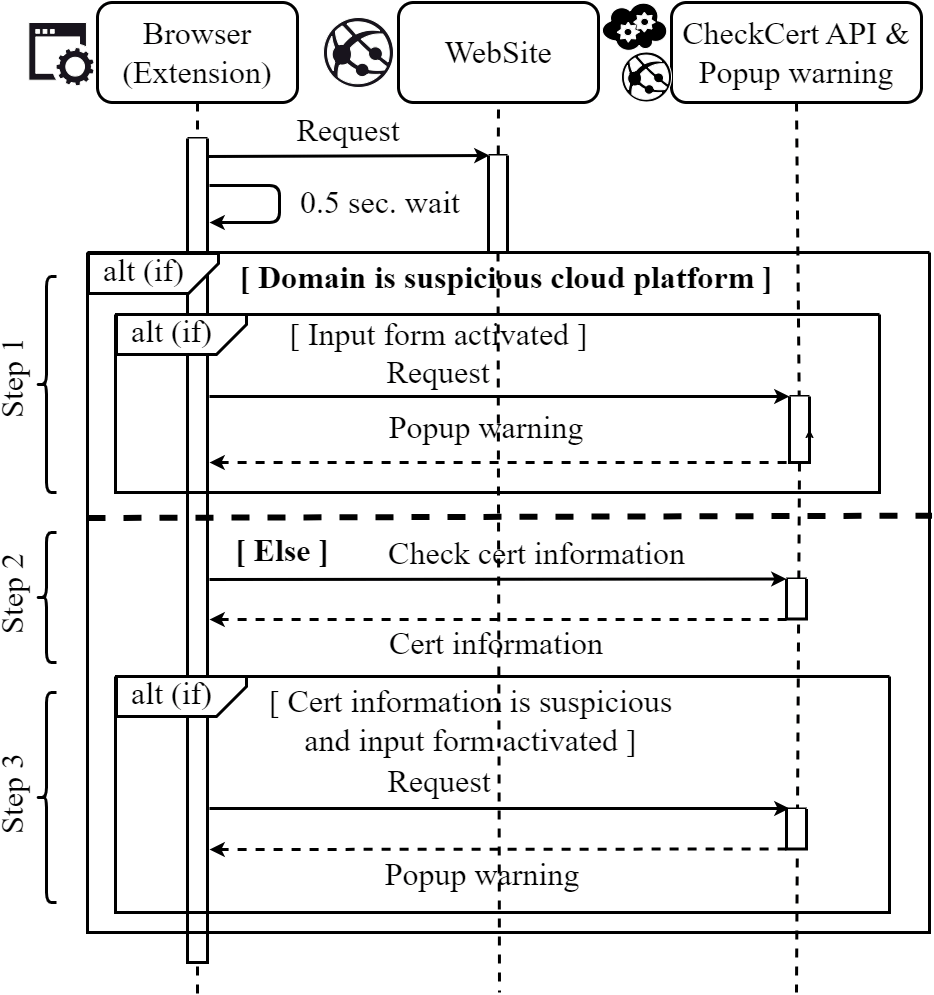

The extension is developed based on the Chrome extension Manifest V3 specification, as Google has decided to phase out Manifest V2 [34]. However, Manifest V3 has strong limitations on extension functions. Manifest V3 extension cannot be access notBefore and NotAfter information that determines the certificate validity period. Therefore, we developed CheckCertAPI to access the notBefore and NotAfter information that determines the certificate validity period of the websites. The extension follows a three-step process, and the user only needs to install one extension. (Fig. 3):

- (1)Detects suspicious SaaS or PaaS and display warning.

- (2)Retrieves the website's certificate information.

- (3)Displays warning if certificate has a short validity period.

This extension runs when the user accesses the website in the browser. In the Figure, the response corresponding to the browser's web request is not shown, but this is because the extension is running in the background and is not designed to wait for a response and operate sequentially. Since the extension focuses on the user authentication form, it sets a wait time until the form is expected to be loaded.

In Step 1, the extension detects specific services and displays a warning message when suspicious activities are found in free-tier services of legitimate SaaS and PaaS platforms, as these are frequently exploited for phishing. This step was added to reduce false negatives because we confirmed many examples of phishing being carried out on SaaS and PaaS platforms during the early stages of the experiment. Moreover, in order to reduce false-positives as much as possible, a warning is displayed when the user authentication form is activated. In Step 2, the extension sends the information about the accessing domain to the external API we built, and obtain the certificate validity period. In Step3, if certificate validity period is less than or equal to 90 days, the extension popup warning when the user authentication form is activated.

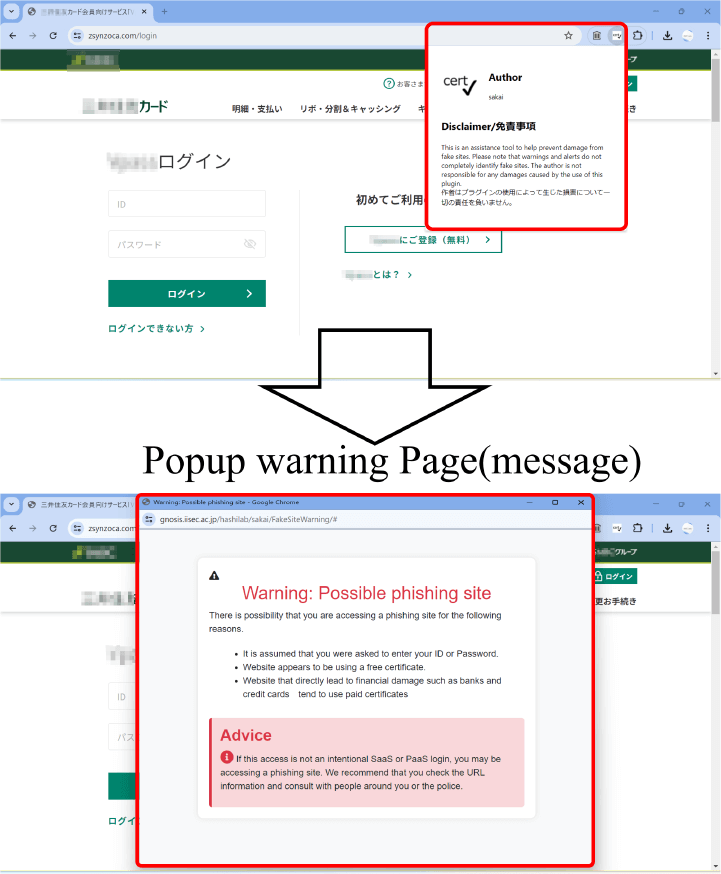

Show the screen shot of installing a browser extension and detecting phishing sites when the user authentication form is activated. The pop-up temporarily suppresses user input and warns you in a large, easy-to-understand red color so that anyone can notice(Fig. 4). In this study, it has not been verified what should be the best way to warn the user, and this is a future work.

Additionally, since the extension is designed to work when accessed by an actual user, it is not affected by evasion functions such that checks whether the user accesses from searching engines [35].

4.2 PoC Experimentation

The proof-of-concept (PoC) browser extension was evaluated using a random sample of 100 entries, consisting of 30 from OpenPhish, 40 from fake shopping sites, and 30 from researcher-identified sites. Since sites from OpenPhish and those identified by researchers had a very short lifespan, the dataset included a slightly larger proportion of fake shopping site data, which was relatively easier to collect.

To analyze the confusion matrix and detection rate of the extension, we conducted detection experiments on 100 legitimate sites with user authentication forms, including banks, credit card companies, shopping sites, cryptocurrency registrants, Japanese public organizations, and highly ranked sites on AkaRank [36], which differed from the data collection process for certificate observations.

While our evaluation was limited to 100 phishing sites due to their short lifespan (many of the 1,047 originally analyzed sites were no longer accessible during testing), this study demonstrates the practical feasibility of the approach. The sample size, though not sufficient for statistical generalization, provides valuable insights into real-world deployment challenges and effectiveness patterns. Our evaluation focused on two key aspects: the detection performance against real-world phishing sites and the practical usability of the extension. The following section presents our comprehensive evaluation results and comparative analysis with existing solutions.

5. Evaluation

5.1 Performance Evaluation and Comparative Analysis

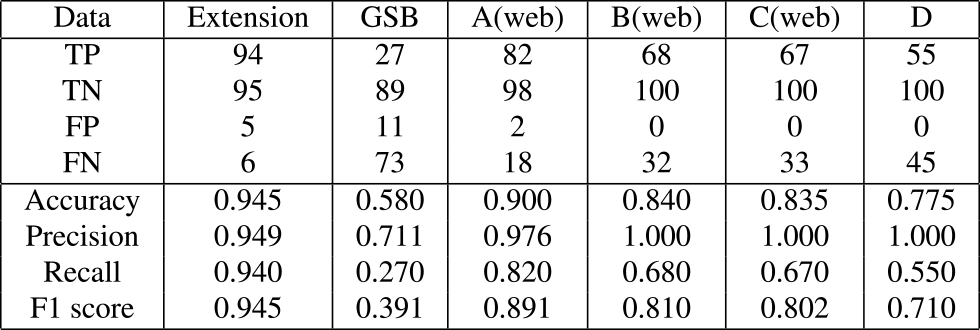

To contextualize the performance of our proposed method, we compared it with several existing phishing detection products, including Google Safe Browsing(GSB) and other commercial solutions. For GSB and web-based products, cases where results could not be obtained were counted as detection failures, as these tools failed to provide protection in such instances (Table 4).

Our method demonstrated superior performance in detecting phishing sites, as evidenced by the high number of true positives (94) and low number of false negatives (6). This highlights the effectiveness of our approach in correctly identifying phishing sites, which is crucial for real-time protection of users. In comparison, the other solutions had significantly higher numbers of false negatives, ranging from 18 to 73, indicating a greater risk of missing actual phishing attempts.

In particular, our method significantly outperformed GSB in terms of recall (0.940 vs 0.270). This suggests that our approach is more effective at identifying a larger proportion of actual phishing sites, which is critical for protecting users from potential threats. GSB's low recall indicates that it may be missing a substantial number of phishing sites, leaving users vulnerable to attacks. The proposed method also achieved a high F1 score of 0.945, surpassing all other tested solutions. The F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced measure of a model's performance. This result underscores the overall effectiveness of our approach in both identifying phishing sites and minimizing false positives.

While some commercial solutions achieved slightly better results in terms of true negatives and false positives, our method still maintained a high level of accuracy in correctly classifying legitimate sites (95 true negatives). The false positives were primarily limited to login pages of specific services, including major platforms like Google and Facebook, new cryptoasset exchanges, and some government offices. False positives on government office login pages suggest a need for these entities to adopt paid certificates [37], aligning with security best practices.

These results demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach in providing real-time and accurate detection of phishing sites, while maintaining a good balance between sensitivity and specificity.

5.2 Overhead Evaluation

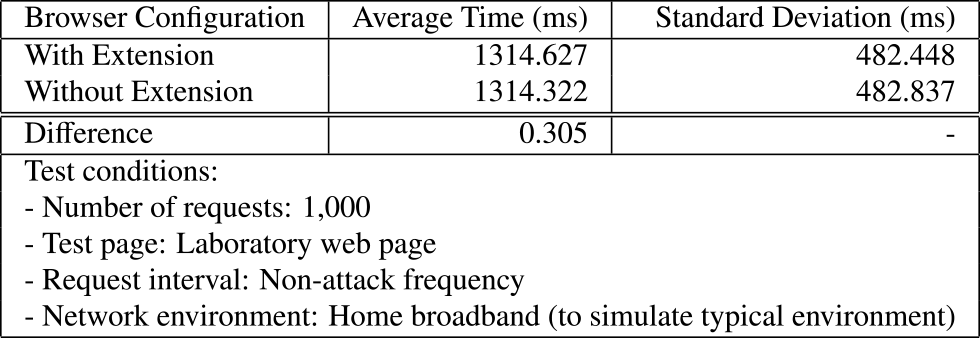

To evaluate the extension's impact on browser performance, we measured page load times with and without the extension enabled. The experiment involved 1000 alternating requests to our laboratory web page, a simple HTML page of approximately 7.8 KB in size, maintaining a non-attack frequency. To ensure realistic conditions, the test pages were accessed from a residential enviroment.

Results showed a minimal difference in average load times (0.305 ms) and comparable standard deviations (Table 5), indicating the stability and consistency of the extension's performance impact. The low standard deviation values (482.448 ms with extension, 482.837 ms without) suggest that the extension does not introduce significant variability in page load times, ensuring a consistent user experience.

Across the 1000 requests, the maximum observed load time with the extension enabled was 3367.310 ms, while the minimum was 391.250 ms. Without the extension, the maximum and minimum load times were 4138.900 ms and 386.550 ms, respectively. These results further confirm the negligible overhead introduced by the extension, as the differences between the maximum and minimum values are not substantial.

These findings demonstrate that the extension efficiently performs its core functions without introducing significant overhead, ensuring a seamless integration into the user's browsing experience. The minimal impact on page load times, combined with the low variability in performance, makes the extension a practical and reliable solution for real-time phishing detection.

These performance characteristics demonstrate that our approach achieves its goal of providing real-time phishing detection without compromising the user experience, though several important considerations remain regarding its practical deployment and long-term effectiveness, as discussed in the following section.

6. Discussion

6.1 Strengths and Limitations of the Proposed Approach

While our approach demonstrates significant potential, it's important to acknowledge both its strengths and limitations for a comprehensive evaluation.

Strengths:

- (1)Simplicity and effectiveness: By focusing on easily observable characteristics like certificate validity periods, we've created a lightweight solution that can be readily deployed and used by a wide range of users.

- (2)High detection rate: Our experiments demonstrated high accuracy in detecting phishing sites.

- (3)Economic barrier for attackers: Obtaining paid long-term certificates to evade detection would significantly increase costs for attackers, making such evasion attempts economically unfeasible for most phishing operations.

Limitations:

- (1)Technical limitations:

- ・Limited scope of observations: Our current approach doesn't consider other potential indicators of phishing, such as website content or URL structure. But we do not claim our approach is the silver bullet. We can add feature to test such indicators for more efficiency.

- ・Other malicious sites: Because the system focuses on user authentication forms to reduce false positives, malicious sites like technical support scams without user authentication forms cannot be detected. We plan to tackle malicious sites other than phishing as a separate research topic. but we are researching malicious sites other than phishing as another future work.

- (2)Implementation constraints:

- ・Mobile Environment Limitations: Our browser extension approach is currently limited to desktop environments, which represents a significant constraint given that mobile devices account for the majority of web traffic. While the underlying detection principles (certificate validity analysis) remain applicable to mobile platforms, implementation would require platform-specific approaches. This limitation should be considered when evaluating the method's comprehensive applicability.

- ・Privacy considerations: While the extension needs to send certificate information to our external API for validation, we have designed it with privacy in mind. The system only processes certificate data without storing IP addresses or domain information, minimizing potential privacy impacts.

- (3)Future challenges:

- ・Potential for false positives: Legitimate sites using short-term certificates could potentially be flagged incorrectly. But we think short-term certificates are rarely used by legitimate sites that are targeted for phishing.

- ・Adversarial Adaptation: If this method gains widespread adoption, attackers may adapt by obtaining longer-term certificates. However, this would significantly increase their operational costs and reduce the disposable nature of phishing infrastructure. We acknowledge this as an evolutionary pressure that may require method refinement over time.

- ・Discussion of certificate shortening: CA/B Forum is moving toward shortening the certificate validity period to 47 days as proposed by Apple, Google, and Mozzila. However, free certificates are moving even shorter, to six days, and this difference leads us to conclude that the method of combining a user authentication form and a certificate will remain effective for the time being.

6.2 Theoretical and Practical Implications

Theoretically, this study contributes to the understanding of phishing tactics by revealing patterns in certificate usage and authentication form deployment that characterize phishing operations. Practically, our research offers a new tool for cybersecurity professionals and everyday internet users. The browser extension provides an additional layer of protection that complements existing security measures. Moreover, the insights gained from our observations of phishing site characteristics can inform policy makers and certificate authorities about potential areas for improvement in the certificate issuance and management process.

This research also emphasizes the potential of simple, certificate-based approaches for real-time phishing detection. By focusing on easily observable characteristics, we've demonstrated that effective anti-phishing measures can be developed without relying on complex machine learning models or extensive computational resources. This approach could serve as a foundation for developing similar tools tailored to other regional contexts or specific types of phishing threats.

6.3 Cost-Effectiveness and Deployment Considerations

The practical deployment of our approach involves minimal infrastructure requirements compared to complex machine learning-based solutions. Based on the lightweight design of our browser extension and the scale of phishing damage in Japan, we estimate the cost-effectiveness as follows:

Implementation Costs: The browser extension requires minimal development resources, utilizing standard web technologies (JavaScript, Chrome Extension API) without specialized hardware or training datasets. The external certificate validation API can be implemented using commodity cloud services, with estimated monthly operational costs of under $100 for moderate-scale deployment serving up to 10,000 users.

Potential Impact: Given that phishing-related damages in Japan reached 540.9 billion yen in 2023 [7], even a modest 1% reduction in successful attacks through early detection could prevent damages worth 5.4 billion yen annually. Our detection rate of 94.5% suggests significant potential for damage mitigation.

Deployment Scenarios: The approach is particularly suitable for:(1) Corporate security departments seeking lightweight supplementary protection, (2) Educational institutions requiring user-friendly security awareness tools, and (3) Financial organizations needing real-time customer protection without performance degradation.

Scalability Considerations: Our certificate-based method offers inherent scalability with minimal maintenance overhead, making it accessible to organizations with limited cybersecurity resources.

7. Conclusion

This study proposed a certificate-driven approach to phishing detection, motivated by our observation that 89.8% of phishing sites used certificates valid for 90 days or less. By combining this characteristic with user authentication form monitoring, we developed a method for real-time detection of potential phishing sites.

Our implementation as a browser extension demonstrated strong effectiveness, achieving a 94.5% detection rate in experimental evaluation. While this approach offers advantages in terms of simplicity and real-time detection compared to existing solutions, we acknowledge its limitations regarding potential false positives and sensitivity to evolving certificate practices.

Future research will focus on three key areas: enhancing the detection mechanism through integration of additional certificate-based metrics, improving accuracy through refined authentication form analysis, and expanding the approach to address emerging phishing tactics. These improvements, supported by long-term empirical studies, will aim to strengthen the method's resilience against evolving threats while maintaining its simplicity and effectiveness.

Acknowledgment This work was supported in part by the JSPS/MEXT KAKENHI under Grant 24K14956.

References

- [1] Morgan, S.: Cybercrime to cost the world $10.5 trillion annually by 2025. Cybercrime Magazine, Vol.13, No.11 (2020).

- [2] Safer Internet Association: [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.saferinternet.or.jp/〉.

- [3] JC3(Japan Cybercrime Control Center): Statistical information on malicious shopping sites, etc. (first half of 2023), [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.jc3.or.jp/threats/topics/article-515.html〉.

- [4] Anti-Phishing Working Group: Inc, Phishing Activity Trends Reports, [Online]. Available: 〈https://apwg.org/trendsreports/〉.

- [5] JC3: Techniques used by phishing attacker groups pretending to be domestic banks, et,c., [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.jc3.or.jp/threats/topics/article-347.html〉.

- [6] National Police Agency in Japan: Concerning the rapid increase in the number of fraudulent remittances caused by internet banking, which appear to be caused by phishing. [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.npa.go.jp/publications/statistics/cybersecurity/data/R5/R05_cyber_jousei.pdf〉.

- [7] JCA(Japan Consumer Credit Association): [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.j-credit.or.jp/〉.

- [8] Rutuja P., Gagandeep K., Himank J., Ayush T., Soham J., Keshav R. and Dr Amit S.: “Machine learning approach for phishing website detection: A literature survey”, Journal of Discrete Mathematical Sciences and Cryptography, 25, pp.817–827. 10.1080/09720529.2021.2016224 (2022).

- [9] Sameen M., Han K. and Hwang S. O.: PhishHaven―An Efficient Real-Time AI Phishing URLs Detection System, in IEEE Access, Vol.8, pp.83425–83443 (2020), doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2991403.

- [10] National Institute of Information and Communications Technology(NICT): TLS Cipher Settings Guidelines, [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.ipa.go.jp/security/crypto/guideline/gmcbt80000005ufv-att/ipa-cryptrec-gl-3001-3.1.1.pdf〉.

- [11] Server Certificate WG (CA/B Forum): Voting Period Begins: SC-081v3: Introduce Schedule of Reducing Validity and Data Reuse Periods[Online]. Available: 〈https://groups.google.com/a/groups.cabforum.org/g/servercert-wg/c/bvWh5RN6tYI〉.

- [12] Internet Security Research Group (ISRG): We Issued Our First Six Day Cert, [Online]. Available: 〈https://letsencrypt.org/2025/02/20/first-short-lived-cert-issued/〉.

- [13] Das Guptta, S., Shahriar, K. T., Alqahtani, H. et al: Modeling Hybrid Feature-Based Phishing Websites Detection Using Machine Learning Techniques, Ann. Data. Sci., 11, pp.217–242 (2024) 〈https://doi.org/10.1007/s40745-022-00379-8〉.

- [14] Maurya, S., Saini, H. S., and Jain, A: Browser extension based hybrid anti-phishing framework using feature selection. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, Vol.10, No.11 (2019).

- [15] Asiri S., Xiao Y., Alzahrani S. and Li T.: PhishingRTDS: A Real-time Detection System for Phishing Attacks Using a Deep Learning Model,Computers & Security,2024,103843, ISSN 0167-4048, 〈https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2024.103843〉.

- [16] Ruofan L., et al.: “Less Defined Knowledge and More True Alarms: Reference-based Phishing Detection without a Pre-defined Reference List”, 33rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 24) (2024).

- [17] Taofeek, Agboola Olayinka: Development of a Novel Approach to Phishing Detection Using Machine Learning, ATBU Journal of Science, Technology and Education, Vol.12, No.2, pp.336–351 (2024).

- [18] Ivan, T., et al: Hunting malicious TLS certificates with deep neural networks. Proceedings of the 11th ACM workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security (2018).

- [19] Vincent, D., and Meyer, U.: Certified phishing: taking a look at public key certificates of phishing websites, Fifteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS 2019) (2019).

- [20] Zheng D., et al: Beyond the lock icon: real-time detection of phishing websites using public key certificates, 2015 APWG Symposium on Electronic Crime Research (eCrime), IEEE, (2015).

- [21] Dinny, K., et al: Phishing Domain Detection Using Machine Learning Algorithms, International Journal on Advanced Science, Engineering & Information Technology, Vol.15, No.1 (2025).

- [22] Sakurai, Y., et al.: Discovering httpsified phishing websites using the tls certificates footprints, 2020 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), IEEE, (2020).

- [23] Cisco Talos Intelligence Group (Talos): PhishTank, [Online]. Available: 〈https://phishtank.org/〉.

- [24] OpenPhish: OpenPhish, [Online]. Available: 〈https://openphish.com/〉.

- [25] Dun&Bradstreet Inc., D&B Hoovers: [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.dnb.com/products/marketing-sales/dnb-hoovers.html〉.

- [26] Ito, D., Takata, Y. and Kamizono, M.: Money Talks: Detection of Disposable Phishing Websites by Analyzing Its Building Costs, 2022 IEEE 4th International Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security in Intelligent Systems, and Applications (TPS-ISA), Atlanta, GA, USA, pp.97–106 (2022), doi: 10.1109/TPS-ISA56441.2022.00022.

- [27] Sakai, K., et al: “Research on trend analysis of fake sites targeting Japan”. Computer Security Symposium 2023 Proceedings: pp.596–603 (2023).

- [28] Ammar A., et al: Phishing Website Detection With Semantic Features Based on Machine Learning Classifiers: A Comparative Study, IJSWIS, Vol.18, No.1, pp.1–24 (2022) 〈https://doi.org/10.4018/IJSWIS.297032〉.

- [29] Sakai, K., Takeshige, K., Kato, K., Kurihara, N., Ono, K. and Hashimoto, M.: An Automatic Detection System for Fake Japanese Shopping Sites Using fastText and LightGBM, in IEEE Access, Vol.11, pp.111389–111401, LetsEncrypt (2023) doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3323218.

- [30] KesagataMe(@KesaGataMe0), X(formerly Twitter), [Online]. Available: 〈https://twitter.com/kesagataMe0〉.

- [31] Internet Security Research Group (ISRG), About Let's Encrypt, [Online]. Available: 〈https://letsencrypt.org/about/〉.

- [32] Cloudflare, Inc., Free Plan Overview, [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.cloudflare.com/ja-jp/plans/free/〉.

- [33] Cloudflare, Inc., Validity periods and renewal, [Online]. Available: 〈https://developers.cloudflare.com/ssl/reference/certificate-validity-periods/〉.

- [34] Google LLC, Manifest V2 support timeline, [Online]. Available: 〈https://developer.chrome.com/docs/extensions/develop/migrate/mv2-deprecation-timeline?hl=ja〉.

- [35] Kodera H., Koide T., Chiba D., Aoki K. and Akiyama M.: Understand-ing attacks with fake shopping websites, IPSJ Journal, Vol. 62, No.9, pp.1523–1535 (2021) (In Japanese).

- [36] Akamai Technologies, AkaRank Website Rankings, [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.akamai.com/security-research/akarank〉.

- [37] Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. In local governments regarding information security policy Guidelines (September 2018 version), [Online]. Available: 〈https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_content/000575052.pdf〉.

Keisuke Sakai completed a master's program in Physics at Tokyo University of Science in Tokyo Japan in 2010. Master (physics). In 2023, he also completed a master's program at the Institute of Information Security in Kanagawa Japan. Master (Informatics). Since 2018, he has been engaged in technical support and research work related to information security at a government agency, and since 2023 he has been a researcher of the Hashimoto Laboratory.

Kosuke Takeshige worked for seven years in the private sector as a software engineer prior to joining the police department. Since 2010, he has been a cybercrime investigator for a police agency. After being dispatched to the Japan Cybercrime Countermeasures Center (JC3), he is currently in charge of investigating cybercrimes while also belonging to the Hashimoto Laboratory as a visiting researcher at the Institute of Information Security. His main interests include cybersecurity, software engineering, and artificial intelligence.

Shingo Matsugaya received M.E. degrees from Institute of Information Security in 2012. He is currently served as a senior engineer in Trend Micro Inc from 2016. His current research interest includes cybersecurity, OSINT and malware analysis. He is also a staff of Japan Cybercrime Control Center (JC3).

Makoto Shimamura received his B.E. degree from the University of Electro-Communications in 2005, and M.E. and Ph.D. degrees from Keio University in 2007 and 2010, respectively. He is currently served as a senior threat researcher in Trend Micro, Inc. from 2017. His current research interest includes cybersecurity, OSINT and malware analysis. He is a member of IPSJ and ACM.

Masaki Hashimoto served as an associate professor at the Institute of Information Security from 2014 to 2023. During this time, he was also an academic visitor at the Information Security Group, Royal Holloway, University of London from 2014 to 2015. Currently, he holds the position of associate professor in the Faculty of Engineering and Design and the Graduate School of Science for Creative Emergence at Kagawa University, a role he has assumed since 2024. He is a member of IPSJ, IEICE, JSSST, and IEEE.

採録日 2025年8月5日